This morning, I stepped outside to take a picture of the little daisies blooming in our yard, thinking that they might make a nice header image, and was confronted by this:

Sweet, but the sight elicited a “shit” from me—more on this below—but it, ironically, is a perfect lead into what I wanted to write about today: regardless of how long you’ve been gardening, you are always learning about your growing space. And, once you think you know it, something will change.

(Sidebar on deer. This is the first deer I’ve seen in our community in the more than 30 years we’ve lived here. We live alongside cougars, wolves, and black bears and they come into town on occasion—just last month there was a cougar a few yards away from ours—and I always assumed they hung out at a narrowing of the peninsula at the far end of our community and picked off any deer that might wander by, heading towards town. [Our neighbouring community, Ucluelet, has lots of deer. And, consequently, lots of fences.] I’m fine living with predators—we’re aware and we behave accordingly. I’m glad they’re out there. But the sight of a deer in my unfenced, plant-filled, yard fills the gardener in me with dread. I know I can build a fence, but I also need a new roof.)

Mapping the sun

On occasion, I help teach a course for novice gardeners. Growing is challenging here, with over three metres of rain annually, clay soils, foggy summers, and slugs—and now deer, sigh—so the course tries to set people up for success by starting with the crops that grow well. One of the first things we encourage people to do is to track the movement of the sun across their growing space. I thought I knew my space well after gardening in it for over 30 years, but the last time we asked the students to do this exercise, I did it too.

The exercise reinforced what I’ve always known—that my vegetable gardens are on the wrong side of the yard. Well, sort of.

Here’s how the yard looked when we bought the place in 1991:

Those overgrown garden plots are on the right-hand side of the yard. Logical at the time since it was the flat side, but, 30 years on, so much has changed. Namely, the poorly maintained cedar “hedge” that was sort of on a shared property line has grown into a poorly maintained row of trees, and it’s very dark in that corner. But, yeah, it’s the flattest space. Here’s how that same vantage looks as of five minutes ago:

Gone is the “pompous grass” fountain; in have come a couple of greenhouses, an arbour, four cut flower beds, and a lot of other bits and bobs. Once I did that sun experiment, I, duh, clued into the fact that the main part of our lawn—once reserved for lolling about with my kids and playing croquet and badminton—was one of the sunniest spots. The kids are gone, so I doubled down with cut flowers and added four beds that get sun for most of the day. (I just built them lasagna-garden-style, on top of the lawn, so they’re easy to remove if and when I choose to, perhaps if and when there are again littles to loll around with.) What I grow in those shady garden plots has changed, too. Greens love our cool climate, so they’re great for chard, kale, sorrel, lettuce, and such; peas are fine, too, and there’s enough light and heat in the summer for beans. Strawberries, rhubarb, and cascade berries seem to do fine as well.

When lawn becomes lake

The size of trees and shaded areas aren’t the only thing that has changed in my growing space. It’s definitely getting wetter. Saying “it’s wet here” is an understatement—we get, on average, three to four metres of rain a year and climate change seems to be making wets wetter. So, a mucky yard is hardly surprising and the back left corner of our yard has always been wet, especially in winter. It has clumps of common rush (Juncus effusus) and every spring a few skunk cabbages (Lysichiton americanum) poke their bright yellow spikes up. I’ve started to add in a few moisture-loving shrubs like ninebark and red osier dogwood, but have otherwise left that spot be.

But the amount of water we’ve got in our yard has definitely increased. Here’s what our lawn ephemeral lake looked like during the most recent atmospheric river.

The water also pools along the entire property line, out of the frame. The hardening our yard probably hasn’t helped—there are the two greenhouses and a wonky wooden deck and falling down playhouse just out of the picture—but we’ve purposely avoided any other hard surfaces on the property to ensure good drainage. What really made the difference to the size of our wetland was when our neighbours to the uphill side of us (three owners ago) cemented all of their garden paths and paved their driveway. Their backyard is sloped and the gardener at the time was in love with rhododendrons, so it’s a rhodo wonderland, all connected with cement paths. (He did it all himself despite being quite debilitated by a stroke; I remember his little cement mixer whirring away.) Ever since then, the water has drained the hillside that rises to the west, and slooshes over that property to settle in ours.

So, all to say, get to know your growing space. Then watch it change!

Where once were salmon

About 12 years ago, we had a water line leak start somewhere between our house and the road, where the services join the property. I didn’t notice it—there was no water pooling on the lawn and no change in our water availability. But one day, there was a knock on the door. A young guy from our village’s public works department asked me if I was currently running any water. I wasn’t, so he walked me out to our water metre, which was happily spinning away. This led to contractors having to dig up part of our yard to make the repair.

During the repairs, I had another knock at the door. Another young man asked me to come with him. He pointed to where they were digging and showed me the hood of a car. I remember it clearly, the smooth metal hood and the two spaces where the headlights had been, now filled with dirt.1

I called the man who had moved our house into this location 40 years prior and told him we’d found the hood of a car. “Oh, yeah,” he laughed. “We buried so much shit in that yard.” That fact probably explains why water, even when it pools like in the image above, drains quickly, and why we have all sorts of crazy hummocks and dips in our yard. That “shit”—probably more metal junk and lots of wood—has been slowly decaying. (It’s the same in the schoolyard across the street which was developed the same year this property was. Divots large enough to fit a small child occasionally open up in the playground as the wood below rots away.)

Casually, the mover of my house added, “Did you know there used to be salmon in your yard?”

No, I did not. But as I thought about this conversation over the next few days, a lot of things clicked into place. Our intermittent wetland with its marsh-loving native plants, being one, of course. Another was a fairly regular stream of water flowing across a sidewalk a few yards from ours—a place that’s slightly downhill. (The flow over the sidewalk is so constant during winter that I’ve called the village twice, thinking a water main had broken.) It must be the natural drainage off our part of the block. Then a friend told me that her grandmother’s house, just a block and a half between our place and the ocean, once had a stream alongside. It would have easily connected to our yard.

My last “clue” is really just a guess, but I like to think it’s true: Whenever there is a bear around, it seems to move from town through our yard and across the street to the forest. Is this ursine wisdom, passed from mother to cub, generation to generation, following the watercourse that once flowed here?

British Columbia is known for its mighty rivers, once filled with salmon. But the province was once also rich with smaller streams, some, like “mine,” just a few hundred metres or so long.2 Each riffle, stream, and wetland had a distinct salmon run, most of which have been lost to development. Including, as I learned, to build the downtown core in the small coastal town in which I live.

So, what to do with this knowledge? I can’t bring back the salmon, but I can, perhaps, let that corner of the yard revert back to more native habitat. I’ve been wanting to cut out the invasive holly, now a massive tree, for years—no doubt our neighbours, and their small children running barefoot, will approve of that—and I’m curious to see what will take root if we stop mowing and just let it be for a while. I’ll report back.

As for the deer, I put the word out this morning when I first started writing this post and have been hearing about other sightings in town over the past few weeks.

Like the salmon, deer were here first. Unlike the salmon, we’ve created some pretty lovely deer habitat, in which they thrive. We need a new roof, but once that’s done, I’ll start socking money away for a fence.

I’m curious … what have you learned about the land you now live on? Let’s start a conversation in the comments.

Thanks for hanging out at Café Botanica. Everyone is welcome and my writing is not behind a paywall, so you can subscribe for free.

If you’d like to support my work financially, feel free to buy me a virtual cup of coffee or a packet of seeds. (Or a fence post!)

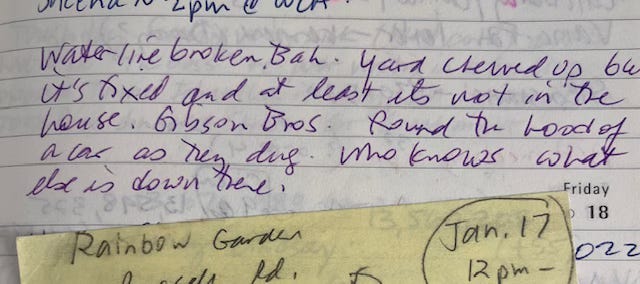

I say I remember it clearly—and I do and I often repeat this story—but one day I started to question myself. Why didn’t I take a picture? Did this really happen or did I just imagine it and have told the story so many times that I started to believe it? (My husband, an obvious corroborator, was away working in Nunavut.) Finally, I dug out my old journals looking for evidence and there it was. (As a writer, I’m appalled at how few details I recorded though!)